Vincent van Gogh painted 35 self-portraits, all in the three-and-half years before he died. In a new exhibition sponsored by Morgan Stanley, 16 of those paintings reveal as much about the artist’s creative journey as they do about his inner life.

Few artists have painted themselves as many times as Van Gogh did. Was he a narcissist who loved his own image? Did his state of mind compel him? Or was he simply his own best model?

By bringing 16 of these portraits together for the first time, Van Gogh Self-Portraits at The Courtauld provides some answers. “Van Gogh’s self-portraits are the lens through which we view him and project ideas onto him—ideas about genius, passion, struggle, mental health, sacrifice, resilience and commitment,” says Karen Serres, the exhibition’s curator and Curator of Paintings at The Courtauld. “More so than those of any other artist, Vincent van Gogh’s paintings, and especially his self-portraits, are read through the filter of his unique and compelling biography.”

Says Franck Petitgas, Morgan Stanley's Head of International, "This exhibition showcases some of Van Gogh's most stunning paintings made during a time when he was experimenting with new styles as well as ways of constructing his own identity and presenting himself to the outside world. The range of portraits, many of which are brought together for the first time from major collections around the globe, allow us to consider his extraordinary life, as well as his work, and how the two are inextricably bound."

Van Gogh Self-Portraits, part of The Morgan Stanley Series, is the first-ever exhibition devoted to Van Gogh’s self-portraits. Together, the works allow us to trace the development of the artist’s signature style, which evolved in a relatively short amount of time. The exhibition includes his earliest self-portrait, made in Paris in 1886, to one of the last, painted at the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in September 1889.

Exploring Styles and Personas

These works allowed Van Gogh to try on various personas and attempt to depict an interior state of mind; they also allowed him to explore new techniques without relying on (or paying for) models. While the subject of these paintings—with its green eyes, red beard and ginger hair—is easily identified by the public, so is the arresting and unique style Van Gogh created through these self-portraits.

When Van Gogh moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo in 1886, he had been a painter for six years but had not created any self-portraits. During his stay in the European capital of the avant-garde, he saw many Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist paintings. Intrigued by the artists’ use of pure color applied to canvas in small daubs, Van Gogh started dabbling with this style, using himself as the model. Jettisoning the rich, dark tones associated with Rembrandt and other seventeenth-century Dutch portraitists, Van Gogh also began incorporating brighter colors into his own work. He made ample use of reds and greens—conveniently his own coloring—as well as blues and oranges, applying these complementary colors next to each other to create dynamic backgrounds. In a very short time, Van Gogh had lengthened his brushstrokes to create a greater sense of energy and vibrancy.

A Change of Place, a New Awakening

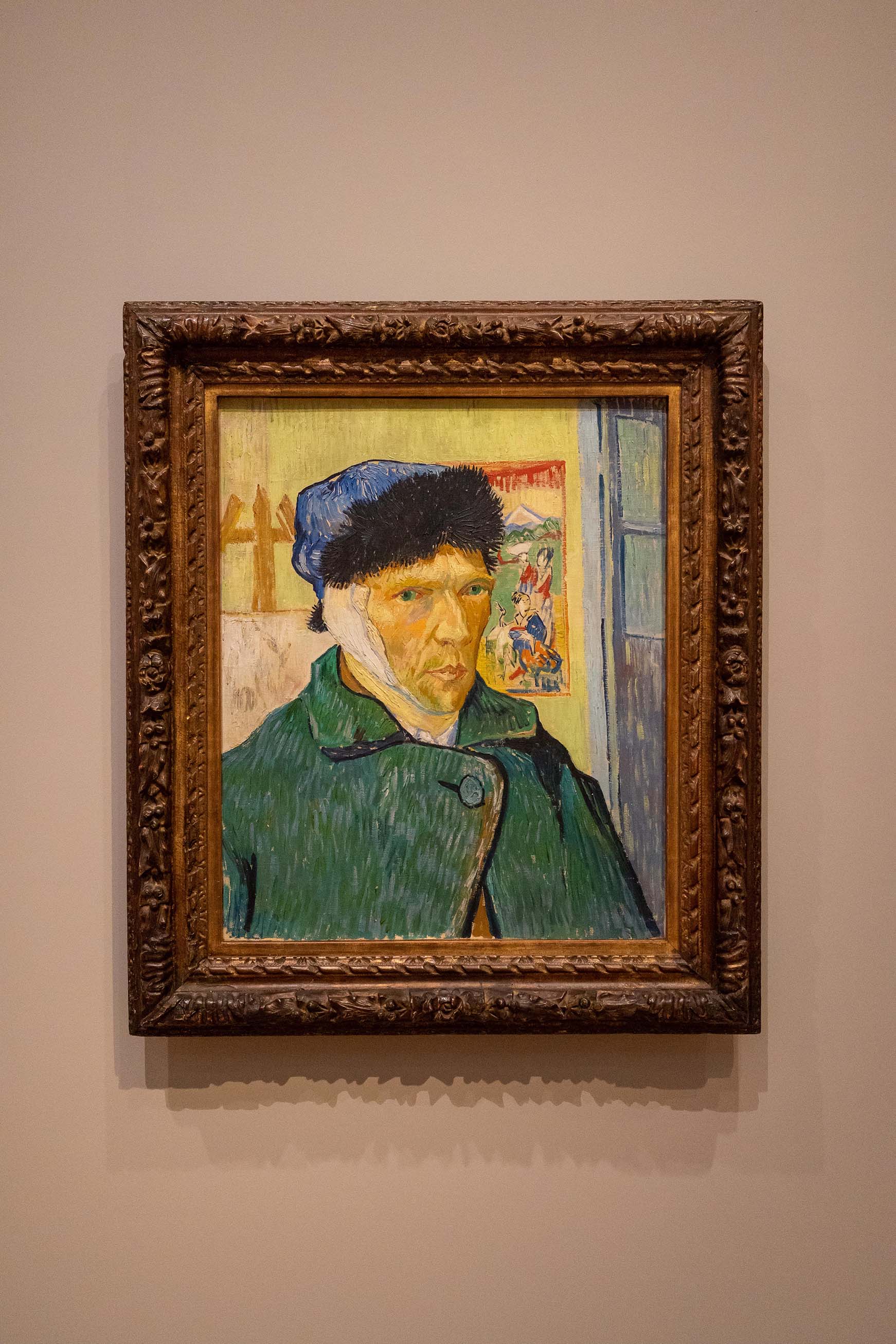

Two years and twenty-seven self-portraits later, Van Gogh moved from Paris to the sunny South of France, where he found his artistic voice: the distinct color palette and brushstrokes combined with the flattened space of his beloved Japanese woodblock prints. In January 1889, he painted the famous self-portrait in his studio in Arles after the moment that defined his life in the public’s imagination.

This self-portrait, says curator Karen Serres, “shows his boldness as a painter as well as his resilience as a human being.” Upon returning from a two-week stay in the hospital after mutilating his ear and suffering a mental crisis, Van Gogh presented himself foremost as artist who had returned to work: a canvas on an easel is visible in the background. Rather than ignore the repercussion of his actions, he confronted it head on, showing the large bandage that covered his wound, which is held in place by a heavy, fur-lined cap.

During his two years in the South of France, Van Gogh painted many landscapes but only eight self-portraits, three in the final year of his life. Van Gogh admitted himself to an asylum in a former monastery outside of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence and suffered several mental health crises. It was during a two-week period in the fall of 1898 that he produced these three self-portraits; the exhibition reunites two of these final works, which were last seen together at the asylum in 1890.

Although he had recently suffered a psychotic break, the second of the two paintings is carefully constructed, relying on a darker, muddier palette. Van Gogh used five different shades of blue in his painter’s smock, flesh tones and background. His brushstrokes and color choices were bold and assertive. As in earlier works, he presented himself as a robust and physically healthy artist, clasping a palette in one hand and confidently holding the viewer’s gaze

Van Gogh would die by suicide less than a year later, at only thirty-seven years of age. Although he is often remembered for his tortured life, Van Gogh Self-Portraits reminds us that he was an ambitious and pioneering artist who used self-portraiture to hone his artistic vision.