An exhibition at The Morgan Library & Museum chronicles the enduring popularity of the monster and the woman who conceived it.

She was 18 years old and in a scandalous relationship with a married man, with whom she had run off at age 16. She had already lost a child and was pregnant with her second. And yet Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley started writing “Frankenstein,” which was published in 1818—when she was 20—and became an instant literary hit. Today, it is widely credited as the first work of science fiction, a genre dominated by male writers.

Shelley’s inspiration? A nightmare. “I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion,” she wrote some years later.

To mark the 200th anniversary of the novel, The Morgan Library & Museum in New York is hosting an exhibition, “It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200,” from Oct.12 to Jan. 27; Morgan Stanley is the lead corporate sponsor. Among the treasures on display is Mary Shelley’s annotated first edition of the book, then titled “Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus,” which was purchased in 1910 by John Pierpont Morgan Sr.

That first edition was published anonymously, though subsequent editions bore the name of the author, whose literary fame in her lifetime was dwarfed by that of the man she eloped with: Percy Bysshe Shelley, the eminent Romantic poet.

How did "Frankenstein," a cerebral tale and Gothic thriller, come to be a pop culture touchstone, a Hollywood obsession, and a staple of so many high school English classes? “There's something about the creation scene, and the idea of making a creature anew without giving birth, that people find endlessly fascinating and inspiring," says Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger, Co-Curator of “It’s Alive!” at The Morgan Library & Museum and Curator of the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle at The New York Public Library, which is co-sponsoring the exhibition.

The Frankenstein story is so adaptable, so capable of interpretation.

‘Demoniacal Corpse’

It was a rainy summer at Lake Geneva in 1816, and Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley spent it with several friends, including the poet George Gordon Byron, who suggested that each of them write a ghost story. She was the only woman who participated, and the only one whose contribution had staying power.

The story was disruptive in Shelley’s time and has continued to fascinate ever since: How science student Victor Frankenstein assembled a human form from exhumed body parts and brought it to life, only to see the creature turn on him and murder his bride on their wedding night. Shelley’s tormented narrator, who is considered the original mad scientist, bemoans “the demoniacal corpse to which I have so miserably given life.”

After it was published, the book was quickly adapted for the stage and has subsequently been made into myriad plays, movies, comic books and TV shows. “One of the arguments of the exhibition is how a novel that is very philosophical in tone and pitched in a way to a highly cultivated audience suddenly took off,” says John Bidwell, the Co-Curator and Astor Curator and Department Head of The Morgan Library’s Printed Books and Bindings Department.

The Morgan Library & Museum, a stately complex of buildings on Madison Avenue at 36th Street, began as the private library of John Pierpont Morgan Sr., whose son donated it to the public in 1924. Known to friends as Pierpont, Morgan Sr. was not only a banker and financier—the founder of the company to which Morgan Stanley also traces its roots—but also a collector of art and books.

“It’s an honor and a pleasure to be able to sponsor such an engaging and well-researched exhibition, particularly in light of our company’s shared origins with The Morgan Library & Museum,” says Kathleen Naughton, Managing Director and Global Head of Events and Conferences. “The firm is committed to celebrating the accomplishments of women in many fields, and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was a literary prodigy and pioneer.”

Highbrow and Lowbrow

The exhibition shows off Frankenstein-related artifacts both highbrow and lowbrow. The iconic image of Boris Karloff as the monster—in the 1931 movie “Frankenstein” and 1935 “Bride of Frankenstein”—has done much to burnish the creature’s image in the public’s imagination, and Bidwell and Denlinger, as part of their three-year quest to gather artifacts for the exhibition, found what they say is the only surviving copy of an advertising billboard for the 1931 film.

Also included is a wig that is a replica of the distinctive hairdo—a dark beehive streaked with white lightning bolts—worn by Elsa Lanchester in the “Bride of Frankenstein.” Perhaps the scariest item is a model of the stitched-up face and torso of the Frankenstein monster as played by Robert De Niro in the 1994 movie version.

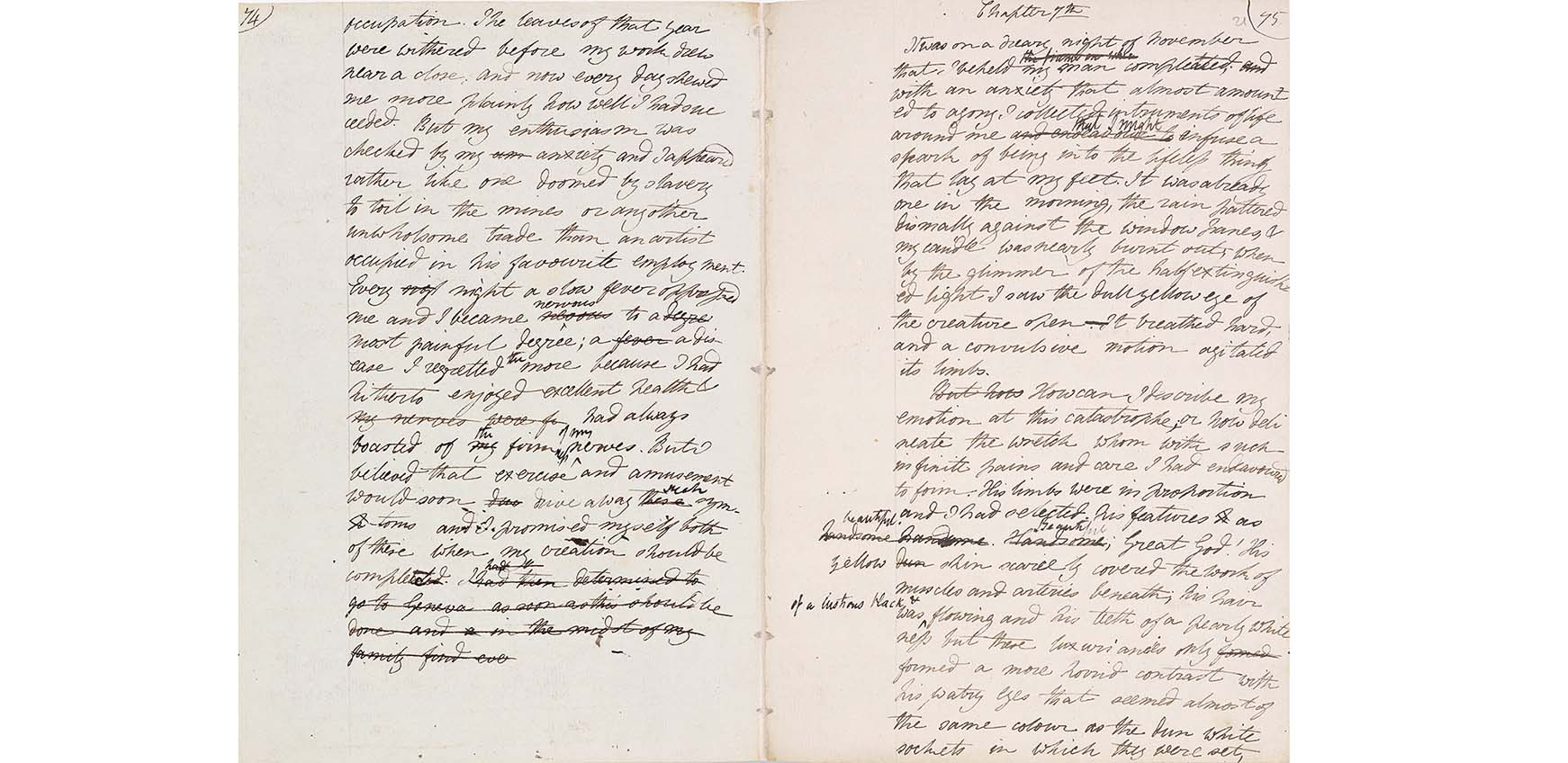

There are pages from Mary Shelley’s original manuscript, which are on loan from the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. From the Detroit Institute of Arts comes the 1781 painting “The Nightmare” by Henry Fuseli, who was a friend of Mary Shelley’s parents. They, too, were literary stars: William Godwin was a writer and anarchist, and Mary Wollstonecraft (who died days after her daughter Mary was born) was a writer and feminist.

Halloween tends to be an important day for Frankenstein fans, and this year will be big: In honor of the 200th anniversary, an initiative called Frankenreads—a project of the Keats-Shelley Association of America—has arranged for public readings of selections from the novel at 100 institutions in 20 countries. The Morgan will be hosting one of them.

“The Frankenstein story is so adaptable, so capable of interpretation,” says Bidwell of The Morgan. “The story is appealing on so many levels, it’s hard to imagine it ever going out of style.”